MBA Alumnus Takes a Deep Dive Into His Passion for Finding Underwater Wrecks

Brett Eldridge poses with his with his rebreather, headed out to find new wrecks in San Diego. Eldridge, who obtained his engineering and MBA degrees at Cal Poly, has performed deep dives around the world, exploring plane and ship wrecks. (Photo courtesy of Brett Eldridge)

Trapped inside a collapsing World War II Japanese oil tanker at the bottom of the ocean in Palau, Brett Eldridge feared the worst.

I’m going to die in this wreck, he thought.

The two exit paths out of the ship had collapsed, and with near-zero visibility due to stirred-up silt, there was no escape in sight.

Fortunately, for a man whose cybersecurity career hinged on risk assessment, Eldridge and his fellow explorers had prepared for a variety of challenging scenarios — and, as a result, had enough oxygen in their rebreathers to survive the extra three hours needed before a fellow diver found and rescued them.

“Given the amount of time and the depth we were trapped inside that wreck, even without panicking, we would have run out of gas on regular scuba equipment,” said Eldridge (Electronic Engineering, ’89, MBA ’95). “But we do as much as we can to reduce the risk.”

Divers illuminate the deck on the Britannic, a steamship that sank after hitting a German naval mine in 1916. The Britannic, which became a World War I hospital ship, rests 400 feet beneath the ocean surface. (Photo/Brett Eldridge)

Since that frightening experience two years ago, Eldridge — a cybersecurity pioneer and award-winning underwater photographer — continues to dive around the world, sometimes discovering long-lost wrecks. Meanwhile, the startup veteran passes his risk assessment lessons on to students who hope to launch businesses through Cal Poly’s Center for Innovation & Entrepreneurship, said Tom Katona, the CIE’s academic director.

“To raise capital for a startup, entrepreneurs need to build a compelling vision around a company that can generate large returns for the investors while simultaneously working to minimize the risk associated with that venture,” Katona said. “Brett is an invaluable source in working with students to help them think strategically about both of these aspects of positioning one’s entrepreneurial venture.”

Eldridge grew up mostly in San Pedro, California, where he spent summers at the beach. While pursuing his undergraduate degree at Cal Poly, he took a diving class in Santa Barbara. But it would be some time before diving became a passion.

After working as an engineer on military radar systems for four years, he returned to Cal Poly to earn an MBA. While pursuing his master’s degree, a course on intellectual property law led him to the emerging cybersecurity field.

“This guy named Phil Zimmermann had created a free encryption program for people to encrypt data and letters so the government couldn’t decipher them, and he used an algorithm in there that was patented,” said Eldridge, a history buff. “I thought it was fascinating. He was also under criminal investigation by the government for violating export controls. The concepts and the history of cryptography plays into World War II.”

Self-taught in cybersecurity, after grad school, Eldridge became involved in several startups, including One Secure, which he co-founded, and Palo Alto Networks. While his career entailed a lot of international travel, he didn’t use those opportunities to dive.

“My entire life was the startup,” he said. “So I didn’t do much diving through most of my work career.”

After “semi-retiring” in 2017, Eldridge began dedicating more time to his burgeoning passion, first during vacations. Eventually, the Orange County resident became trained in technical diving, which allows deeper diving, exploring inside wrecks, underwater caves and other places beyond the reach of sport diving.

Brett Eldridge, diving with an iceberg in Antarctica. (Photo/Becky Kagan Schott)

Tech diving is also more dangerous, requiring considerably more preparation and equipment.

Hoping to connect the dives to history, Eldridge began looking into diving for undiscovered wrecks – mostly downed war planes and ships — and teamed with veteran wreck diver Tyler Stalter, who has dove some of the most famous wrecks, including the Andrea Doria and the USS Monitor.

“I first met Brett during COVID,” said Stalter of San Diego. “I had been looking for someone to dive targets with for several years, and Brett is always willing to ‘go take a look’ at something no matter where it is.”

Once the pair decided to seek new wrecks, their hunts would take them around the world: Eldridge has performed dives in Antarctica, Greece, Bikini Atoll, Croatia and the Solomon Islands, among others.

Recently featured on an episode of Discovery’s “Expedition Unknown,” a television series that investigates iconic unsolved events, lost cities, buried treasures and other puzzling stories, Eldridge writes extensively about his dives on his blog, Wrecked in My Revo.

“We’ve identified or found somewhere in the neighborhood of 20 wrecks in Southern California,” Eldridge said.

One of his favorite explorations involved the Britannic, an 882-foot steamship that sank after hitting a German naval mine in 1916. Built by the same company that had created the ill-fated Titanic, the Britannic had been used during World War I as a hospital ship.

As the Britannic began to sink with the bow first, two of the ship’s lifeboats were launched prematurely, against the captain’s orders. Filled with passengers, the boats drifted toward the ship’s massive propellers, which were out of the water, and shredded the boats, killing all 30 people in them.

If something goes wrong, you need to just deal with it quickly and not spend a lot of time to think about it

Brett Eldridge

“They’re big,” said Eldridge, whose photo of the props provide a sense of scale. “And props, when they’re out of water, are going to spin faster.”

The ship, discovered by Jacques Cousteau in 1975, still lays bombed and broken about 400 feet below the surface of the Aegean Sea.

For Eldridge, the dive was a long-fulfilled dream.

“I spent years and years training and getting ready for it,” Eldridge said.

While Satler’s primary role on dives entails studying the ocean floor for anomalies, Eldridge prepares equipment and chronicles the dives with photos. While shooting underwater is technically complicated, there is also limited time to capture everything, especially on deeper dives.

After a 6-minute descent using an underwater scooter, due to the extreme depth, he only had 30 minutes to explore each time he dove the Britannic. As Eldridge adjusted his camera’s manual settings for light and began taking photos, he also had to remain aware of his surroundings.

“It’s a very extreme kind of photography,” Eldridge said. “And if your buddy needs you, you need to be there. There’s a whole litany of things that can go wrong.”

Preparation helps improve muscle memory, he said.

“If something goes wrong, you need to just deal with it quickly and not spend a lot of time to think about it,” he said.

With enough photos, Eldridge creates detailed models of the wrecks using technology known as photogrammetry.

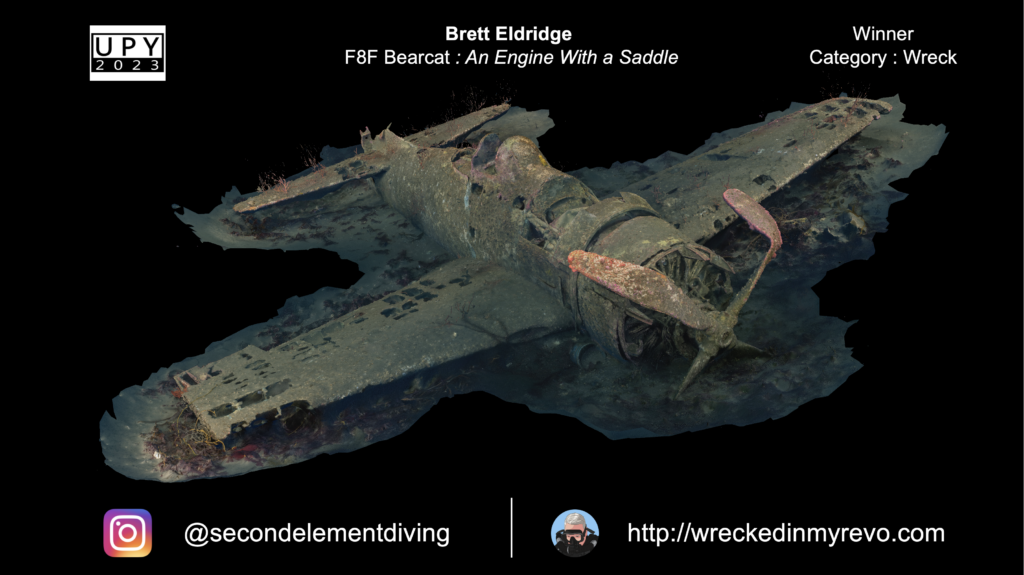

Brett Eldridge won first place in the Wreck category of the 2023 Underwater Photographer of the Year contest for this model he created using photos he took. The model depicts a F8F-1 Bearcat that lies on the ocean floor off of Point Loma, Calif. (Brett Eldridge)

“You take thousands of two dimensional photos and you put them into software … and if you do it correctly, it will build a three-dimensional model,” Eldridge said.

One model he created of a newly discovered plane wreck they identified off San Diego’s Point Loma won the 2023 Underwater Photographer of the Year contest in the Wreck category.

“Brett has a unique specialty of photogrammetry in austere environments,” Stalter said. “Whether it be in deep water, limited visibility, remote, he can get the job done.”

His photos of the IJN Sata, the Japanese oil tanker sunk in 1944 by American bombers in the western Pacific, includes photos that show the deteriorating condition of the ship.

After the frightening dive, the team could use those photos as part of their review of what they did wrong and right.

The biggest “right” was using a rebreather device that recycles unused oxygen. Also, the team didn’t panic, stuck together and communicated — all things Eldridge considers to offset risk.

While most students won’t dive for wrecks, that risk assessment provides a good analogy for his career, which entailed anticipating potential negative scenarios.

Photo gallery: Brett Eldridge has chronicled his deep dives around the world. (Photos/Brett Eldridge)

“It is interesting, that parallel,” he said. “Cybersecurity is all about protecting assets and minimizing risk.”

At his alma mater, Eldridge has been involved with the CIE and teaching an innovation class for roughly a decade.

“When I look at that arc of time, the quality of output that students are coming up with has continued to increase,” he said.

Eldridge acts as a mentor to students, sponsors student awards and regularly is a guest speaker. He typically judges the annual Innovation Quest startup competition, but this year, he had another engagement: a dive in Greece.

Now that he is semi-retired — though he still advises startups — he plans to dive further into his underwater hobby.

“I’ve got four or five projects, some local, some overseas involving things people have never dove,” he said. “I’ve got one warship I’m trying to find that would just be the most epic discovery.”

By supporting Cal Poly’s Center for Innovation & Entreprenuership, you can help students make an impact on California and beyond.